4v291o

Stranger Than Fiction is one of those rare films that quietly reshapes how you look at your life. Not with a heavy hand, but with a gentle, persistent whisper. I first watched it at a time when I felt like my days were melting into each other, caught in the rhythms of routine. It was the kind of film that didn’t just entertain me, it made me pause, reflect, and feel seen.

Will Ferrell, best known for his loud, absurd comedy, gives a performance here that’s beautifully restrained. His character, Harold Crick, is an IRS agent who lives by numbers and routines, counting brush strokes, calculating steps, timing everything. There’s something tragic and strangely relatable about the way he clings to order, as if routine could protect him from the unpredictability of life. And when he starts hearing a narrator in his head describing his every move, and learns that he might be a character in someone else's story… it hit me like a brick. Because haven’t we all felt, at some point, like we’re being swept along by something we don’t quite understand?

There’s a real tenderness in the way the story unfolds. Harold’s slow awakening to the possibility of life, not just existence, but living—is both funny and quietly profound. Maggie Gyllenhaal’s Ana is messy and ionate, the complete opposite of Harold, and the warmth of their connection reminded me of how love often comes when we loosen our grip on control.

What stays with me the most, though, is the idea of authorship, of who gets to write our stories. The film made me realize that even if we feel like we’re stuck in a plot we didn’t choose, we can still shape the ending. Or, at the very least, meet the ending with some sense of dignity and intention. That sounds dramatic, I know but Stranger Than Fiction earns that depth.

It’s not just clever or quirky or philosophical. It’s all of that, but more importantly, it’s human. It’s the kind of film that wraps around you like a soft, strange dream, and then lingers, quietly asking, What would you do if you knew your life was a story? And what if you realized… it already is.

]]>

This review may contain spoilers.

Watching Spirited Away for the second time, I found myself even more enchanted by its dreamlike world, as if rediscovering a half-ed childhood memory. It’s a film that feels like stepping into a space between reality and imagination, where emotions take shape in spirits, bathhouses, and forgotten gods.

The first time I watched it, I was drawn in by the sheer magic of it all. The stunning animation, the strange yet inviting world, and the quiet strength of Chihiro. But this time, it resonated on a deeper level. There’s something incredibly human about Chihiro’s journey, the way she transforms from a frightened girl into someone capable of kindness, courage, and quiet resilience. She’s not a traditional hero; she’s just a child learning to navigate an unfamiliar world, making mistakes, but always choosing to be good.

One of the most beautiful things about Spirited Away is how it never rushes. It lingers in moments of stillness, No-Face quietly offering gold, the gentle presence of Haku, or Chihiro’s train ride across the flooded landscape. That scene, in particular, hit me in a way it didn’t before. It feels like growing up, like moving forward into the unknown, even when the past still clings to you in shadows and reflections.

Rewatching it, I also felt more attuned to its themes. The loss of identity, the fear of change, but also the power of kindness. Yubaba’s bathhouse may be ruled by greed, but it’s moments of selflessness that drive the story forward. Chihiro doesn’t win by force; she wins by understanding, by ing who she is and treating others with care.

It’s a film that, much like its protagonist, changes as you do. The first time, it was an adventure. This time, it felt like a lesson in growing up, in holding on to what matters, even as the world shifts around you. And I have no doubt that the next time I watch it, I’ll find something new, something waiting quietly between the frames, ready to be ed.

]]>

This review may contain spoilers.

I first watched The Hunger Games as a teen, and back then, it hit me like a bolt of lightning. It wasn’t just another blockbuster, it was an awakening to a kind of storytelling that felt raw, intense, and deeply human. Watching it again now years later, I can still feel the same tension in my chest, the same emotional pull that made me fall in love with it the first time.

From the moment Katniss volunteers for Prim, the film grips you with an unshakable sense of urgency. I sitting there, heart pounding, completely swept up in Jennifer Lawrence’s performance. How her eyes alone could carry the weight of an entire world crumbling around her. She’s not some untouchable hero, she’s scared, stubborn, and just trying to survive. And maybe that’s what made her so compelling to me when I was younger, this idea that even when everything is stacked against you, you can still fight, still push forward.

The world of Panem is terrifying, and the way the film builds it up, the districts, the Capitol’s grotesque wealth, the sheer cruelty of the Games it all feels so immersive. Even now, I find myself drawn to those quiet moments, like when Katniss and Rue share a brief, fragile peace in the arena. Rue’s fate shattered me as a teen, and honestly, it still does. That scene, where Katniss sings to her and covers her in flowers, is one of those moments that sticks with you long after the credits roll.

Rewatching it, I also appreciate how much the film trusts its audience. It doesn’t over-explain the horror of the Games or force emotional beats down your throat, it just lets them play out, making everything feel more real. And the shaky, documentary-style camera work? I know it’s divisive, but for me, it adds to the chaos, the feeling that you’re right there with Katniss, breathless and afraid.

Maybe part of why I love The Hunger Games so much is that, at its core, it’s a story about resilience. About a girl who never wanted to be a hero but becomes one anyway. It resonated with me as a teen, and it still does now. Some films lose their magic when you revisit them years later but this one doesn’t. If anything, it’s only grown more powerful.

]]>

I first watched The Breakfast Club as a teenager, and despite being from the UK, I connected with it instantly. It didn’t matter that the film was set in an American high school in the ’80s, its themes of loneliness, self-doubt, and the desire to be understood felt universal.

At its core, The Breakfast Club is about five very different students stuck in detention together, each carrying their own burdens, fears, and insecurities. But as the day goes on, the walls they’ve built around themselves begin to crack, and they see each other not just as stereotypes. the brain, the athlete, the basket case, the princess, the criminal but as complex people. That’s what made it so powerful for me. It captured that awkward, in-between stage of life when you’re trying to figure out who you are while feeling trapped in the roles others assign to you.

There were moments that hit surprisingly close to home. The conversations about parental pressure, feeling invisible, or being misunderstood resonated deeply. Even though I didn’t grow up in an American high school, I knew what it felt like to be pigeonholed, to wonder if people really saw the real me.

The performances are fantastic, and John Hughes' writing is razor-sharp, blending humor with real emotional weight. The final scene, with Judd Nelson’s iconic fist pump, gave me chills the first time I saw it and still does. It’s that perfect moment of defiance, hope, and the belief that, even if nothing changes on Monday, something inside has shifted.

The Breakfast Club remains one of the most honest and timeless portrayals of teenage life I’ve ever seen. Watching it as an adult, I appreciate it even more. It reminds me of that time in my life, messy, uncertain, but full of possibility.

]]>

Watched on Thursday March 20, 2025.

]]>

This review may contain spoilers.

Watching In the Mood for Love for the second time, I found myself even more drawn into its world. Not just visually, but emotionally. The first time I watched it, I was mesmerized by Wong Kar-wai’s intoxicating use of color, light, and movement, as if the entire film were suspended in time, forever caught in a moment of longing. But this time, the emotions hit even harder. The restraint. The unspoken words. The aching beauty of two people who find themselves orbiting each other, knowing they can never truly collide.

There is something devastating about the way Mr. Chow (Tony Leung) and Mrs. Chan (Maggie Cheung) fall into their quiet, melancholic rhythm. At first, their relationship is built on discovery. Realizing their spouses are having an affair and finding solace in each other’s company. But then it turns into something deeper, something more fragile and painful. They rehearse imaginary conversations, pretending to be their unfaithful spouses, but the act only makes the reality of their emotions more unbearable. It’s in these moments that the film devastates me the most. Their love is so pure, yet they refuse to let it become tainted by the same betrayal they have suffered.

I think what makes In the Mood for Love so heartbreaking is how it captures the impossibility of their love. There is no moment of catharsis, no grand declaration, no sweeping embrace. They hold back because they have to. Because that is what people did in 1960s Hong Kong. Because they are trapped by the weight of social expectations and their own moral comes. But that doesn’t make their love any less real. If anything, it makes it even more powerful.

Wong Kar-wai and cinematographer Christopher Doyle frame their world in ways that emphasize distance and separation - doorways, mirrors, narrow corridors. They are always near each other, but never quite together. The slow-motion sequences, set to Yumeji’s Theme, feel like memories unfolding in real-time, as if the film itself is trapped in nostalgia, reliving these moments over and over. I noticed more of these details on my second viewing. The way Maggie Cheung’s qipaos subtly change, the way Tony Leung smokes a cigarette just a little longer, as if lingering in the moment. Everything is so precise, so delicate, so deeply felt.

And then there’s the ending. That crushing, wordless epilogue where Mr. Chow whispers his secret into a hole in the ruins of Angkor Wat, sealing it away forever. The first time I watched it, I thought it was one of the most poetic endings I had ever seen. On this second watch, it felt even more tragic. A love story reduced to a secret, buried in time, never to be spoken of again.

I think this second viewing solidified what I already felt:

In the Mood for Love is a masterpiece. It’s a film that lingers in the heart like a half-ed dream, beautiful and painful in equal measure. It’s about love that almost was, about moments that slip through our fingers, about the way we carry longing with us even when we try to move on. Some films fade from memory after you watch them. But this one stays with you, like a love story you never quite got to finish.

There’s something magical about Porco Rosso. It doesn’t hit with the same emotional devastation as Grave of the Fireflies or the profound nostalgia I have for My Neighbor Totoro but it settles into your soul in a way that only Ghibli films can.

At its core, it’s a story about a man or rather, a pig who’s lost faith in himself and the world around him. Porco, a former ace pilot turned bounty hunter, soars over the Adriatic, catching sky pirates and drowning his sorrows in cigarettes and dry wit. He’s a romantic figure, but a deeply wounded one. He’s exiled himself, both physically and emotionally, from a life he once cherished. And yet, beneath his cynical, tough exterior, there’s a heart that still beats with quiet longing for love, for purpose, for redemption.

Watching Porco Rosso, I was struck by how effortlessly Miyazaki blends humor and melancholy. The film has plenty of thrilling dogfights and whimsical moments (those bumbling sky pirates are an absolute delight) but there’s always an undercurrent of sadness. Porco’s transformation into a pig, his self-inflicted curse feels like the kind of thing that comes from deep regret, a metaphor for survivor’s guilt or a man who no longer believes he deserves to be human.

And yet, there’s hope. Fio, the bright-eyed young engineer, refuses to let Porco wallow in his bitterness. Gina, the elegant singer who’s loved him for years, waits patiently, believing he can still change. Even in a world that’s shifting toward war and despair, there’s still room for beauty, love, and second chances.

I think that’s what makes this film resonate so deeply is it’s a story about finding the will to move forward, even when you feel lost. It’s about the skies we once soared through and the ones we might still reach.

Ghibli films have a way of making you feel like you’ve lived inside them, and Porco Rosso is no exception. It left me wistful, inspired, and yearning for the open sky.

]]>

Drive My Car is not just about grief, love, or art, it’s about the spaces in between, the silences where things unsaid take shape, and the way time itself changes how we carry our past.

At nearly three hours, it unfolds slowly, but never aimlessly. Watching it felt like reading a novel where every sentence carries weight, where the pauses and glances between characters say as much as their words. Yūsuke Kafuku, a theater actor and director, is grieving in a way that feels both deeply personal and eerily universal. He doesn’t seek catharsis through grand gestures, he simply moves forward, carrying the weight of everything left unresolved with his late wife. And then there’s Misaki, his quiet, observant driver, whose own grief runs parallel to his. Their conversations, sparse at first, build into something so unexpectedly profound that by the time the film reaches its quiet climax, I felt as if I had lived through something alongside them.

What struck me most about the film is how much it trusts its audience to sit in discomfort. To let scenes linger, to let emotions swell without an immediate release. There’s something achingly real about that. How often do we actually get the closure we crave? How often do we really understand the people we love before they’re gone? The film doesn’t give easy answers, but it gives something better, an acknowledgment that even in uncertainty, even in unresolved pain, there is still a way forward.

It’s a film that made me reflect on my own life in ways I didn’t expect. The weight of words unspoken. The quiet solace of companionship, even between near-strangers. The way time, when given enough space, can turn grief into something else, not necessarily lighter, but different. Maybe even bearable.

I don’t think Drive My Car is a film for everyone, but for those willing to sit with it, to let it unfold at its own pace, it offers something rare. Not just a story, but an experience.

]]>

Watched on Wednesday March 12, 2025.

]]>

I first watched Catching Fire as a young teen, and even now, years later, it still holds a special place in my heart. There was something about it that gripped me in a way few sequels ever do. Maybe it was the sheer intensity, the way it expanded on the world of Panem, or the way it made me feel like I was right there with Katniss, fighting to survive in a system designed to crush her.

What struck me most back then and still does now is how much darker and more layered this chapter of the series feels compared to the first film. Katniss isn’t just trying to stay alive anymore, she’s a symbol, a spark that the Capitol is desperate to extinguish. Jennifer Lawrence’s performance is phenomenal, capturing Katniss’s trauma, anger, and reluctant heroism with raw authenticity. I feeling so much for her, for Peeta, for Finnick (who instantly became one of my favourite characters), and for all the people suffering under Snow’s rule.

The Quarter Quell arena was terrifying and brilliantly designed. The poison fog, the jabberjays, the spinning cornucopia, it all felt so intense and unpredictable. Even knowing what was coming, I still get chills watching those moments unfold. And that final shot? Katniss, staring straight into the camera, realizing the rebellion has truly begun, that image has never left me.

There’s something timeless about Catching Fire. It’s a story about power, oppression, and defiance that still resonates deeply. Rewatching it now, I can appreciate the nuances more, but it still gives me that same thrill, that same emotional gut punch I felt when I first saw it as a teen. For me, Catching Fire isn’t just a great sequel, it’s the heart of the entire Hunger Games series.

]]>

This review may contain spoilers.

There are some films that feel like gentle whispers to the soul, and Perfect Days is one of them. Having now watched it three times, I find myself loving it more with each viewing. It’s a film that lingers, not just in the mind, but in the quiet moments of daily life, in the way light filters through a window, in the sound of leaves rustling, in the ritual of a simple task done with care.

Wim Wenders has created something truly special here. It’s deceptively simple, following Hirayama, a middle-aged man who cleans public toilets in Tokyo, yet his life feels so full. He wakes up to music on his cassette player, tends to his plants, smiles at the world around him, and takes pleasure in the smallest of things. A ing cloud, a tree’s shadow, a book before bed. It’s not that he’s without sadness, but he carries it with quiet dignity, never letting it define him.

What moves me the most about Perfect Days is how deeply it resonates with a feeling I can’t quite put into words. Maybe it’s the beauty in routine, in embracing life as it is rather than what it could have been. Maybe it’s the way Koji Yakusho’s performance speaks volumes without saying much at all, how his eyes reveal warmth, nostalgia, and even a flicker of pain that makes him all the more human.

By the third viewing, I found myself watching less for the story and more for the details. The light bouncing off a wall, the way Hirayama straightens a picture frame, the rhythm of his work. These little things, often overlooked in life, feel profound in this film. They remind me to slow down, to breathe, to appreciate.

That final scene, with "Perfect Day" playing, hits harder each time. The camera lingers on Hirayama’s face, and in that moment, you feel everything, the weight of his past, the quiet joy of the present, the uncertainty of the future. And yet, there’s a peace in it, a contentment.

Few films have left such a lasting impression on me. Perfect Days is a masterpiece not because it shouts, but because it listens, to life, to time, to silence. It’s a film I know I’ll return to again, because with each viewing, it feels a little closer to home.

]]>

Watched on Sunday March 9, 2025.

]]>

Watched on Saturday March 8, 2025.

]]>

Watched on Wednesday March 5, 2025.

]]>

This review may contain spoilers.

There’s something magical about watching a film for the first time and knowing, deep in your gut, that it’s going to stay with you forever. Spirited Away was one of those rare experiences for me.

I went in knowing its reputation, one of Studio Ghibli’s most beloved films, a masterpiece often hailed as one of the greatest animated films ever made. But nothing could have prepared me for just how deeply it would affect me. From the very beginning, as Chihiro’s mundane world melts into something strange and otherworldly, I felt a childlike sense of wonder I hadn’t experienced in years. It wasn’t just about the breathtaking animation or the meticulous world-building (both of which are stunning) it was the emotions lurking beneath it all, the fear of the unknown, the loneliness of growing up, and the quiet strength that comes from learning to trust yourself.

At first, Chihiro is scared, hesitant, and overwhelmed, much like any child would be when thrown into a world they don’t understand. But as she navigates the bizarre and often intimidating bathhouse, something remarkable happens: she grows. Not in an overt, dramatic way, but in small, meaningful moments, showing kindness to No-Face, standing up to Yubaba, and holding on to her memories of her parents despite everything trying to strip them away. I saw pieces of myself in her, particularly in her initial uncertainty. We’ve all had moments of feeling lost, of being out of place in an unfamiliar world. But Spirited Away reminds us that courage isn’t about never being afraid. it’s about pushing forward despite the fear.

One of the moments that hit me hardest was Chihiro’s farewell to Haku. There was something so bittersweet about it, this fleeting connection, this unspoken bond, and the quiet acceptance that some things, no matter how meaningful, are not meant to last forever. It left me feeling a little hollow, but in a good way, like I had been given something precious and then gently asked to let it go. Their relationship isn’t romantic in the traditional sense, but it carries a deep, almost spiritual weight. It’s about ing, about promises made and kept, and about the kind of love that lingers even after goodbye.

Visually, the film is a feast. Every frame feels alive, from the glowing lanterns reflecting on the water to the way Chihiro’s hair flows in the wind. The bathhouse itself feels like a character, bustling, mysterious, and filled with both wonder and danger. Then there’s Joe Hisaishi’s score, which is nothing short of breathtaking. The music carries so much emotion, from the gentle melancholy of "One Summer’s Day" to the grand, sweeping beauty of "The Sixth Station." The scene of Chihiro and No-Face on the train, sitting in silence as the world drifts past them, is one of the most poignant sequences I’ve seen in any film, animated or otherwise.

I don’t know why it took me this long to watch Spirited Away, but I’m grateful I finally did. It’s not just a great film, it’s a deeply personal one, the kind that makes you reflect on yourself in ways you never expected. It reminds us of the beauty of fleeting moments, the importance of kindness, and the quiet, unshakable resilience that lies within all of us. I have no doubt I’ll revisit it again, and when I do, I have a feeling I’ll love it even more.

]]>

Few films capture the beauty and brutality of nature with the raw emotional depth of Princess Mononoke. Hayao Miyazaki’s 1997 epic is not just a masterpiece of animation, it’s a profound meditation on humanity’s relationship with the natural world, told through breathtaking visuals, complex characters, and a deeply moving story.

At its heart, Princess Mononoke is a tale of conflict and coexistence. The young warrior Ashitaka, cursed by a demonic spirit, embarks on a journey to find a cure, only to find himself caught in the struggle between industrial progress and the natural order. Lady Eboshi, the leader of Iron Town, is a fascinating antagonist. Not a villain in the traditional sense, but a pragmatic and comionate leader who seeks to build a better life for her people, even if it comes at the cost of the environment. On the other side stands San, the titular "Princess Mononoke," a fierce warrior raised by wolves who fights to protect the forest and its spirits.

Miyazaki avoids simple black-and-white morality, crafting a world where every character has their own motivations and justifications. This complexity is what makes the film so powerful, there are no true heroes or villains, only individuals trying to survive in a changing world.

Visually, this film is stunning. The animation is rich with detail, from the lush landscapes of the forest to the fluid, kinetic action sequences. Joe Hisaishi’s hauntingly beautiful score elevates the film’s emotional weight, making every moment resonate even deeper.

Beyond its artistry, the film’s themes remain more relevant than ever. The battle between industry and nature, the consequences of human greed, and the hope for balance in a world of destruction,these ideas feel even more urgent today.

In the end, Princess Mononoke is a breathtaking, deeply moving experience that stands as one of Miyazaki’s greatest achievements. It’s not just a film, it’s a legend, a fable, and a call to understand and respect the world around us. A true masterpiece in every sense.

]]>

Watched on Tuesday March 4, 2025.

]]>

American Pie 2 holds a special place in my heart, not just as a sequel but as a film that takes everything fun about the first and refines it into something even more entertaining. I first watched the American Pie movies as a teenager, binging through them during a summer break, and this sequel stood out as the most enjoyable of the bunch. Rewatching it now in my mid-20s, I can still appreciate why it clicked with me so much back then.

The film picks up a year after high school, with the gang reuniting for one last summer together before adulthood creeps in. There's something about that transitional period, the fleeting nature of those carefree days that resonates even more now than it did when I first watched it. The beach house setting makes everything feel like an endless summer adventure, and the dynamic between the characters feels smoother and funnier than in the first film. Jim’s desperate attempts to prepare for Nadia, Stifler’s wild antics, and the classic misadventures of Finch all deliver some of the best laughs of the series.

What I think American Pie 2 does better than its predecessor is its balance of humor and sincerity. The first film had its heart in the right place, but it was mostly about losing virginity as a rite of age. This one expands beyond that, it’s about friendship, change, and realizing that nothing lasts forever. There’s a bittersweet edge to the film that I didn’t fully appreciate as a teenager but hits harder now.

Of course, it’s still an American Pie movie, meaning it’s filled with outrageous moments like Jim’s superglue disaster, the classic you go then we go scene, and Stifler being, well, Stifler. But these moments don’t just feel like crude jokes for the sake of it, they actually work within the story’s tone and the characters’ growth. And honestly, American Pie 2 has some of the best comedic timing in the series.

That said, while I find it better than the original, it’s still not a masterpiece. The humor is very much of its time, and not every joke has aged well. Some characters, like Kevin, feel a bit lost in the mix, and the plot is more episodic than tightly structured. But despite its flaws, I can’t deny how much fun I have every time I watch it.

Watching American Pie 2 now brings back a flood of nostalgia for those lazy summer days of my own youth, where everything felt possible, and friendships felt eternal. It may not be a perfect film, but for me, it’s the best of the series, one that captures the feeling of being young, stupid, and trying to hold onto something special before it slips away.

]]>

This review may contain spoilers.

Grave of the Fireflies is an emotional experience, one that I won’t forget anytime soon. I knew its reputation before watching it, but nothing could have prepared me for just how devastating, how deeply human, and how profoundly moving it would be.

From the very beginning, Isao Takahata’s 1988 masterpiece sets a melancholic tone. The film opens with the haunting image of a boy, Seita, dying alone in a train station. His spirit watches over his own lifeless body as fireflies flicker in the darkness. This is not a hopeful war film, nor one that glorifies sacrifice, it is a tragic, deeply personal story about two siblings struggling to survive in the final days of World War II.

Seita and Setsuko are, without exaggeration, some of the most heartbreakingly real characters I’ve ever encountered in animation. Their love for each other is pure and beautiful, making the film’s descent into despair all the more unbearable. After an American firebombing raid leaves them orphaned, they are forced to navigate a world that is cruel and indifferent. Their relatives treat them as burdens, food is scarce, and with each ing day, survival becomes more of a distant dream.

The animation, as expected from Studio Ghibli, is stunning, but unlike the whimsical fantasy of Miyazaki’s works, here it serves a different purpose. The beauty of nature, the warm glow of the fireflies, the soft watercolor backgrounds, everything is contrasted with the horror of war and human neglect. One of the most heartbreaking sequences for me was when Seita tries to cheer Setsuko up with a firefly lantern, only for her to later bury the dead fireflies in a tiny grave, innocently comparing them to their deceased mother. That moment broke me. It’s a small, quiet scene, yet it carries an unbearable weight.

The way the film portrays suffering is gut-wrenching, but what makes Grave of the Fireflies so powerful to me is how it never feels manipulative. It doesn’t rely on exaggerated melodrama. Instead, it presents suffering with an unflinching honesty, letting the tragedy unfold naturally. The pain is raw, but so are the moments of love and tenderness between Seita and Setsuko. Their laughter, their games, their small joys, they make the inevitable all the more heartbreaking.

By the time the film reached its final moments, I was in tears. Seeing Setsuko’s tiny, malnourished body, her innocent hallucinations of food, her quiet ing, it was almost too much to bear. Seita’s grief, his desperate attempt to give her some happiness even in their final days, left me shattered. And then, to see his own fate, dying alone and forgotten was just as painful.

I think what makes Grave of the Fireflies so devastating isn’t just the fact that it’s a war film, but that it’s so deeply personal. This isn’t about generals or soldiers, it’s about children. It’s about the ones who suffer the most in war, the ones who are left behind, the ones who never asked for any of it. And the most painful part? Seita and Setsuko’s fate wasn’t inevitable. They didn’t die because of bombs or gunfire. They died because of indifference.

It’s rare to find a film that affects me so deeply, but this one did. It’s not something I can watch often, but I know I’ll carry it with me forever. Grave of the Fireflies is more than just a film, it’s a heartbreaking elegy, a reminder of the cruelty of war, and a testament to the power of love in the face of hopelessness. It’s a masterpiece, one that left me in tears, and one I will never forget.

]]>

Watched on Friday February 28, 2025.

]]>

There’s something haunting about Donnie Brasco that I didn’t expect. On the surface, it’s an undercover cop story set in the world of the mafia, but underneath, it’s really about the slow erosion of identity. It’s about a man who steps into a role so convincingly that he starts to forget where the act ends and where he begins. There’s no glory in it, no real sense of triumph, just the quiet, creeping realization that some lines, once crossed, can’t be undone.

Johnny Depp plays Joe Pistone, an FBI agent who infiltrates the mafia under the alias Donnie Brasco, but the real emotional anchor of the film is Al Pacino’s Lefty Ruggiero. Pacino has played big, loud, and operatic gangsters before, but here, he’s subdued, almost pitiful. Lefty is a low-level, weary soldier who has spent decades following orders, never rising through the ranks. He sees Donnie as his shot at something more, maybe not power, but at least respect. And that’s where the tragedy kicks in, because we know from the start that this can only end badly for him.

There’s a slow, creeping sadness throughout the film. Joe starts the movie with a wife and kids, but as he sinks deeper into the role of Donnie, he drifts further from them. There’s a scene where he goes home for Christmas, but he’s distant, like a ghost in his own house. His wife (Anne Heche) begs him to come back to reality, to be the man she married, but the line between Joe Pistone and Donnie Brasco is already too blurred. That hit me hard. It made me think about how easy it is to lose yourself in something, even with good intentions. You tell yourself it’s temporary, that you’re in control, but by the time you realize how deep you’ve gone, there’s no clean way out.

I wouldn’t say Donnie Brasco is one of my all-time favorites, but it’s a film that lingers. It’s subtle in its heartbreak, and by the time the ending rolls around, you feel the weight of everything that’s been lost. The final scene, with Lefty taking off his jewelry before heading out to his fate, is one of the quietest yet most devastating moments in any crime film I’ve seen.

If you go into it expecting a Goodfellas-style rise-and-fall gangster story, you might be surprised. This one’s not about glory or even the high life of the mob, it’s about the cost of loyalty, the pain of betrayal, and how sometimes, the person you betray the most is yourself.

]]>

Few films have ever made me reflect on my own life as profoundly as Ikiru. Kurosawa's masterpiece isn’t just about death, it’s about what it means to truly live. I didn't expect an old black-and-white Japanese film about a dying bureaucrat to shake me, but it did.

Takashi Shimura’s performance as Watanabe is haunting. The way he conveys decades of regret in a single glance hit me harder than I expected. Watching him shuffle through his days, drowning in the monotony of meaningless work, I saw a reflection of fears I’ve had myself—of time slipping away, of waking up one day to realize I never really lived. And yet, Ikiru isn’t a film about despair. It’s about the quiet but defiant act of choosing to live, even when time is running out.

It’s a quiet film, not in of silence but in its approach. It doesn’t rush, doesn’t beg for attention. It simply observes, and in doing so, it forces you to do the same. I found myself thinking not just about the characters on screen but about my own life, my own choices. There’s something profoundly human about Ikiru, in the way it captures the weight of existence, the fear of time slipping away, and the desperate search for meaning in the mundane.

By the time the film ended, I wasn’t left with sadness but with a quiet determination. It’s the kind of film that lingers, not because of any dramatic twist or shocking moment, but because it makes you feel something real. It made me want to live more intentionally, to appreciate the small things, and to not let life slip by unnoticed.

Not every film can change the way you see the world. Ikiru is one of the few that can.

]]>

This review may contain spoilers.

There’s a certain weight to Unforgiven that just stays with you. It’s the kind of film that doesn’t just tell a story, it makes you sit with it, wrestle with it. I first watched it expecting a classic Western, maybe something in the vein of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly or High Noon, but what I got was something far more haunting.

At its core this is a film about time. It’s about how the past clings to you, how violence never truly leaves those who wield it, and how redemption, if such a thing even exists, comes at a cost. Clint Eastwood’s William Munny is a man who has tried to outrun his sins, to bury them beneath a quiet life of pig farming and fatherhood. But when opportunity (or maybe fate) comes knocking, he picks up his gun again, and what follows is less a triumphant return than a slow, grim descent back into the darkness he tried to leave behind.

What struck me most about the film is how it strips away the myth of the gunslinger. There’s nothing glamorous about the killings here. No romanticized duels, no grand shootouts. Just fear, desperation, and the sickening finality of death. The scene where the young Schofield Kid breaks down after his first kill hit me particularly hard. His whole life, he dreamed of being a gunslinger, only to realize that taking a life is nothing like the stories say. That moment, to me, is the heart of the film.

Then, of course, there’s the ending. It’s brutal, inevitable. Munny becomes the very thing he swore he wasn’t anymore, but what choice did he have? The way Eastwood plays that final scene in the saloon so cold, controlled, terrifying... gave me chills. And yet, even after all the blood is spilled, there’s no sense of victory. Just emptiness.

I think that’s why Unforgiven has stuck with me the way it has. It’s a meditation on violence, on regret, on the way history refuses to let go of us. And maybe, in some way, we don’t want it to.

]]>

I first watched American Pie when I was 16, during summer off school. Back then, I absolutely loved it. It was hilarious, outrageous, and felt like the ultimate teen comedy. The characters, from Jim’s painfully awkward moments to Stifler’s over-the-top antics, had me in stitches. It was the kind of movie that made me feel like I was in on some grand joke about adolescence, even if my own teenage years weren’t quite as wild.

Now, in my mid-20s, I still love the film, but I see it differently. It’s no masterpiece, far from it but it holds a special place in my heart. The humor doesn’t always land the way it did when I was younger, and some of the jokes feel a bit dated. But there’s a charm to its ridiculousness, a sense of nostalgia that makes it impossible for me to dislike. It’s still fun, still quotable, and still an iconic piece of late-90s teen cinema.

If 16-year-old me had rated it, it would’ve been a solid 5 out of 5 stars. Now? It’s more of a 3 out of 5 stars. But that’s not a bad thing. It’s a film that reminds me of a time when summer meant freedom, when comedy felt bigger and bolder, and when American Pie was the funniest thing I’d ever seen. And for that, I’ll always have a soft spot for it.

]]>

Watched on Tuesday January 21, 2025.

]]>

Watched on Monday February 24, 2025.

]]>

This review may contain spoilers.

There are some films that feel less like stories and more like places. Places you can return to, where time slows down and the world feels gentler. For me, My Neighbor Totoro is one of those films. It is not just a movie, it is a refuge, a quiet, rain-soaked countryside where the wind rustles through the trees and childhood still holds its magic. Every time I revisit it, I am reminded why it is one of my all-time favorite comfort movies.

From its very first frames it immerses you in a world that feels alive. Hayao Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli craft a vision of rural Japan that is so rich in texture and detail that it never feels like mere animation. It feels like a place you have visited before or a dream you half- from childhood.

The backgrounds are painted with a delicate warmth, filled with endless shades of green, as if nature itself is alive. The way light filters through the trees, the way the wind bends the grass, the way rain splashes onto a dirt road, it’s all rendered with such attention and care that it becomes almost tangible. You can feel the humidity of the summer air, hear the cicadas buzzing in the distance, and sense the cool dampness of a night spent waiting at a bus stop in the rain.

One of the most beautiful aspects of the film’s world is how it moves at its own rhythm, unhurried and observant. The camera lingers on small, ordinary moments:

dust motes floating in an old house, water dripping from the trees, acorns rolling across wooden floors. These details may seem simple, but they are the heart of My Neighbor Totoro. They remind us of the quiet beauty of everyday life, the things we often overlook but are so essential to childhood wonder.

Unlike most animated films, My Neighbor Totoro does not have a conventional conflict. There is no villain, no grand adventure, no looming catastrophe. Instead, it is a story about transition, about two sisters, Satsuki and Mei, moving to the countryside while their mother recovers in a hospital. Their world is filled with uncertainty, but the film does not dwell on fear or sadness. Instead, it embraces curiosity, discovery, and the quiet resilience of childhood.

What makes this film so powerful is how deeply it understands children. Satsuki and Mei feel like real kids, not just characters. They bicker, they get excited over the smallest things, they run barefoot through the grass, they cry when things become overwhelming. Their emotions are raw and unfiltered, and the film never condescends to them. It treats their joys and fears with the same weight and significance as the grandest of epics.

And then, of course, there is Totoro...

Totoro is more than just a character, he is the embodiment of everything warm, safe, and magical about childhood. He does not speak, yet his presence is deeply reassuring. He is massive, yet gentle. He is mysterious, yet familiar. He is a spirit of the forest.

The moment when Mei first curls up on his belly, dozing off as he breathes in slow, steady rhythms, is one of the most soothing scenes in cinema. It is the kind of image that stays with you, something you almost wish you could step into.

And then there’s the bus stop scene, a moment of pure cinematic magic. Satsuki and Mei waiting in the rain, Totoro appearing silently beside them, his fur damp from the drizzle. He doesn't do much, just stands there, listens to the rain, and grins when handed an umbrella but the moment is spellbinding. It captures the feeling of being a child out in the world, experiencing something strange and wonderful, something that no adult would ever believe.

When the film ends, it leaves behind something more than just a story. It leaves a feeling, something warm and nostalgic, something that lingers in the air like the scent of summer rain.

It reminds us of the magic in the ordinary. It reminds us to look at the world with wonder, to listen to the wind in the trees, to watch the clouds drift by. It reminds us of childhood, not in a way that makes us long for the past, but in a way that makes us want to carry that sense of wonder into the present.

For me, My Neighbor Totoro is a masterpiece not because of what happens in it, but because of how it makes me feel. It is a film I return to when I need comfort, when I need to slow down, when I need to the beauty of the world.

And every time I watch it, I feel like a child again, standing in the rain, waiting for something magical to arrive.

]]>

Watched on Sunday February 23, 2025.

]]>

In the Mood for Love is s a film that transcends the boundaries of conventional storytelling in my opinion. Weaving an achingly beautiful tale of love, longing, and restraint. It is a masterclass in visual storytelling, where every frame is meticulously composed, every glance carries weight, and every silence speaks volumes.

At the heart of the film are Chow Mo-wan (Tony Leung) and Su Li-zhen (Maggie Cheung), two neighbors in 1960s Hong Kong who gradually form a deep connection upon discovering their spouses are having an affair. But rather than succumbing to the same betrayal, they navigate their emotions with an almost unbearable restraint, trapped between societal expectations and their own moral boundaries.

What makes it a masterpiece is its cinematography, courtesy of Christopher Doyle and Mark Lee Ping-bing. Every frame feels like a painting, drenched in deep reds, lush greens, and golden hues, evoking a sense of nostalgia and melancholy. Wong Kar-wai’s signature use of slow motion, coupled with the haunting score (particularly the recurring Yumeji’s Theme), enhances the film’s hypnotic rhythm. The camera often frames characters through doorways, reflections, or narrow corridors, emphasizing their isolation and unspoken desires. The use of light and shadow is exquisite, giving the film an almost dreamlike quality, as if we are watching memories unfold.

Beyond its visual splendor, its a profoundly emotional experience. Leung and Cheung deliver performances of remarkable subtlety, conveying years of longing with just a glance or the flicker of an expression. Their chemistry is undeniable, yet their love remains just out of reach, making the film’s final moments all the more devastating.

This is a film that lingers in the mind long after the credits roll. It’s not just about love but about the moments that slip away, the words left unsaid, and the weight of time. In the Mood for Love is cinema at its most poetic. A masterpiece.

]]>

Watched on Saturday February 22, 2025.

]]>

There’s something about At Eternity’s Gate that lingers in the mind long after it ends, like a brushstroke that refuses to fade. It’s less of a traditional biopic and more of an experience, a film that attempts to see the world as Van Gogh might have. I wasn’t just watching Willem Dafoe play Van Gogh, I felt like I was inside his head, seeing through his weary, desperate, yet endlessly curious eyes.

The film is full of movement, handheld cameras that stumble and sway, as if the world itself is unstable, slipping away from Van Gogh’s grasp. There are moments where the light is so golden and alive that I could almost feel the sun on my skin. And yet, there’s always that undercurrent of isolation, of a man who sees beauty everywhere but can never quite belong.

Dafoe is extraordinary. He doesn’t try to imitate Van Gogh so much as embody his soul, his longing, his pain, his hunger for connection. The scenes with Oscar Isaac’s Paul Gauguin crackle with tension, a collision of two artists with different visions. And the moments of solitude, where Van Gogh simply wanders, talks to himself, or frantically paints as if time is running out, are heartbreakingly intimate.

I love how the film embraces uncertainty. It doesn’t pretend to know all the answers about Van Gogh’s death, about his suffering, about what truly drove him. It leaves space for mystery, for interpretation. And maybe that’s what makes it so powerful, it understands that Van Gogh’s life wasn’t just about tragedy, but about an overwhelming, almost unbearable love for the world around him.

When the credits rolled, I just sat there, letting it wash over me. At Eternity’s Gate isn’t a film that hands you easy emotions. It’s one that makes you feel deeply, without always knowing why. And maybe that’s the closest thing to understanding Van Gogh himself.

]]>

Watched on Thursday February 20, 2025.

]]>

Watching Kiki’s Delivery Service a second time was like revisiting an old friend and seeing them in a new light. I already loved it the first time, but this time, I felt its warmth even more deeply. It’s a film that gently reassures you without ever needing to spell it out.. about growing up, finding your place, and learning that losing yourself is part of the process of becoming who you’re meant to be.

Kiki’s journey resonates so much because it’s not about grand heroics but small, quiet struggles, the kind we all go through. The way she doubts herself, the way she feels lonely in a new place, the way she loses confidence in her abilities and has to rediscover them. It all feels so honest. And yet, it’s never heavy. Miyazaki fills every moment with beauty, whether it’s the seaside town’s golden light, the way the wind rushes through Kiki’s hair mid-flight, or the simple comfort of baking bread in a warm kitchen.

Jiji’s humor, Osono’s kindness, Ursula’s wisdom, every character feels like a piece of life’s puzzle that Kiki needs at just the right time. And the music? Pure magic. Joe Hisaishi’s score makes every scene feel like a dream you don’t want to wake up from.

What struck me even more on this second watch was how the film captures the feeling of burnout in such a subtle but powerful way. The way Kiki loses her ability to fly isn’t just a plot device, it’s something deeply relatable. We’ve all had moments where something we love, something that once came so naturally, suddenly feels impossible. Seeing Kiki struggle with that, and then regain her magic by embracing kindness and patience with herself, was more moving than I ed.

And then there’s the way the film portrays solitude. Not as something tragic, but as something necessary. Kiki’s loneliness never feels exaggerated; it’s just a part of life, especially when you’re growing up and stepping into the unknown. There’s a quiet bravery in the way she keeps going, even when she feels lost. That’s what makes her eventual triumph so rewarding. It’s not just about flying again, but about believing in herself.

I love Kiki’s Delivery Service more with each viewing. It’s a masterpiece, not just for its animation but for how it understands what it means to grow, to struggle, and to keep moving forward. Kiki’s story is one I know I’ll return to again and again, and each time, I’ll take something new from it just like Kiki learning to fly all over again.

]]>

Watching Waking Life felt like drifting through a dream I didn’t want to wake up from though sometimes, I wasn’t sure if I fully understood the dream in the first place. It’s a film that doesn’t just tell a story, it invites you into a stream of consciousness where ideas about free will, dreams, and the nature of reality swirl around in beautifully surreal animation.

I won’t pretend I grasped everything Richard Linklater was throwing at me. Some conversations resonated deeply, like the ones about lucid dreaming and existential purpose, while others felt like intellectual rabbit holes that I wasn’t always in the mood to chase. But even when the dialogue felt overwhelming, the film’s rotoscoped animation kept me mesmerized. The way the visuals constantly shift and morph, never staying still, perfectly mirrors that feeling of being lost in thought, of knowing you’re dreaming but not being able to control it.

If Before Sunrise and Chungking Express (two masterpieces I adore) capture the fleeting magic of human connection in the real world, Waking Life does the same in a dreamscape, where conversations happen and dissolve as quickly as they appear. It doesn’t hit me quite as hard emotionally, which is why it falls short of a perfect score, but I love how it lingers in my mind long after watching.

A 4 outta 5 stars feels right to me. It’s a film I ire, one I’ll return to, and maybe, like a recurring dream, one that will reveal something new each time.

]]>

Some horror movies rely on jump scares. Others create an atmosphere of dread. [REC] does both, but it also does something much scarier... it makes you feel trapped.

I went in expecting a typical found-footage horror movie, but within minutes, I was completely sucked into its world. The way it starts so casually, with reporter Ángela Vidal and her cameraman Pablo filming a mundane fire station segment, feels so natural that it lulls you into a false sense of security. But once they enter that apartment building, the sense of realism becomes suffocating. There’s no escape, not for the characters, and not for the viewer.

What makes [REC] so effective is its sheer intensity. The shaky camera work might turn some people off, but for me, it only heightened the immersion. The fear feels raw and unfiltered, especially in the performances. Manuela Velasco as Ángela is incredible, going from bubbly journalist to a desperate survivor in a way that never feels forced. And that final act? The moment they step into that pitch-black attic, I felt like I was right there with them, holding my breath, afraid to move.

It’s rare for a horror film to genuinely get under my skin, but [REC] did. It’s not just scary, it’s relentless. It doesn’t give you a break, and by the time the credits roll, you’re left in stunned silence, still gripping onto whatever’s nearby. I’ve seen a lot of horror, but few movies have ever made me feel as powerless and on edge as this one.

For me, [REC] isn’t just a great horror movie. It’s one of the scariest films I’ve ever seen.

]]>

Watched on Monday February 17, 2025.

]]>

Watching Chungking Express for the second time felt like stepping into a dream I once lived, only to find new colors in its haze. It’s a film that thrives on rhythm, of cty lights flickering, of hearts beating in uncertainty, of time slipping through our fingers like sand. Wong Kar-wai doesn’t just tell a story; he paints longing in neon and rain, in expired pineapple cans and whispered goodbyes.

Both stories, Cop 223 nursing a broken heart through late-night snacks and Cop 663 unknowingly waiting to be saved, hit even harder on rewatch. The first time, I was caught up in the romance of it all, the playful yet melancholic way people drift in and out of each other’s lives. But this time, I felt the weight of loneliness more, the way these characters exist in their own bubbles, yearning for connection yet afraid to grasp it. Faye Wong’s free-spirited presence feels almost mythical, a force of nature that breathes life into 663’s routine, and Tony Leung’s quiet vulnerability is nothing short of magnetic.

What makes Chungking Express a masterpiece is how it captures something so ephemeral yet so deeply resonant. Love, in this world, is fleeting but beautiful. Every frame pulses with longing, every moment feels like a memory in the making. This isn't just a film, it’s a feeling, one that lingers long after the credits roll.

]]>

Watched on Saturday February 15, 2025.

]]>

There’s something deeply fascinating about Barking Dogs Never Bite, Bong Joon-ho’s overlooked debut. It doesn’t have the polish of his later masterpieces, but in a way, that rawness makes it feel more personal, more alive. The film’s dark humor, tangled morality, and unexpected tenderness make it an odd but compelling mix, one that sneaks up on you. At first, I wasn’t sure what to make of it. A story about a struggling academic who takes out his frustrations on noisy dogs shouldn’t be this entertaining, but Bong has a way of turning bleakness into something strangely human. The film moves between absurd comedy and biting social critique, showing a world where frustration festers in tiny, mundane cruelties. And yet, somehow, it never loses its heart.

What lingers with me is not just the biting satire or the unflinching look at class resentment, but the quiet moments of unexpected connection. Bae Doona’s character, a kindhearted but scrappy employee who gets caught up in this bizarre chaos, gives the film its soul. Her determination, her naivety, and her resilience are magnetic. Even in its rougher moments, you can feel the filmmaker Bong Joon-ho would become, his gift for balancing genres, his empathy for outsiders, his knack for finding beauty in the absurd. This film may not be perfect, but it’s strangely affecting to me.

]]>

There’s something deeply comforting about From Up on Poppy Hill. It’s a film that feels like a quiet afternoon spent looking through old photographs, filled with nostalgia, warmth, and a tinge of melancholy. Watching it, I was transported into a world that feels both distant and deeply familiar. an early-1960s Yokohama that is bustling with life, yet also tenderly intimate.

Unlike many Ghibli films that lean into fantasy, this one is grounded in the everyday. What I love most about this film is its atmosphere. The animation is stunning, full of soft blues and golden light that make the seaside town feel alive. The soundtrack, with its jazz and folk influences, makes it feel like you’ve stepped into an old memory. There’s a sense of longing that runs through the film, not just in Umi and Shun’s story, but in the way the world around them is changing. The students fight to preserve their clubhouse while Japan itself is moving forward, caught between the past and the future.

I won’t pretend the story is the most intricate Ghibli has ever told, but that’s part of its charm. It’s a film that lingers in its quiet moments: the smell of breakfast cooking, the rustle of newspapers, the creak of floorboards in the clubhouse. It reminds me of the small, everyday details that make life meaningful.

Maybe that’s why it resonates so much with me. It captures a feeling I can’t quite put into words, something about growing up, about loss, about holding onto what’s precious even as the world moves forward. It’s not a grand adventure, but it doesn’t need to be. Sometimes, a simple story, told with sincerity, is enough to leave a lasting impression.

]]>

This review may contain spoilers.

I went into this knowing it had been remade as The Departed, but what struck me was how different it felt. It’s leaner, sharper, and more restrained. Where Scorsese goes for bombast, Andrew Lau and Alan Mak opt for silence, tension, and a weight that lingers long after the credits roll. This isn’t just a movie about moles infiltrating their enemies, it’s about identity, fate, and the unbearable loneliness of living a lie.

Tony Leung delivers a masterclass as Chan, the undercover cop who’s spent so long embedded in the triads that he’s forgetting who he really is. His eyes tell the whole story. Years of exhaustion, paranoia, and a desperate longing for normalcy. On the other side, Andy Lau’s character (also named Lau) is a mole inside the police force, yet he isn’t played as a typical villain. Instead, he’s complex, ambitious, and perhaps even tragic in his own way. The symmetry between them is mesmerizing. They’re both trapped, both yearning for something they can’t quite reach.

The pacing is tight. There’s no wasted moment, no indulgent backstory. Every glance, every choice, every moment of silence is loaded with meaning. And that rooftop confrontation? Perfection. It’s one of those rare movie moments that stops your heart, even if you’ve seen it before.

Maybe what I love most about Infernal Affairs is its fatalism. It understands that sometimes, no matter how hard you try to escape your past, it clings to you. That final shot, with Lau standing alone, is haunting. He’s won, technically, but at what cost?

]]>

Watched on Tuesday February 11, 2025.

]]>

Watched on Monday February 10, 2025.

]]>

Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker is an unsettling, meditative, and deeply profound journey that lingers in the mind long after the credits roll. From its very first frame, the film establishes an atmosphere of eerie stillness, drawing us into a world where time seems to stretch and reality itself feels fluid.

Visually, the film is nothing short of breathtaking. Tarkovsky’s use of color (shifting from sepia-toned bleakness to lush, vibrant greens within the Zone) is masterful, creating a haunting contrast between the industrial desolation of the outside world and the strange, almost sacred beauty of the Zone. Every shot feels meticulously composed, as if the film is sculpting time itself.

What struck me most was the films philosophical weight. The film never hands you easy answers. Instead, it invites you to sit with its ambiguity, to question the nature of desire, belief, and purpose. The conversations between the three men feel deeply human, filled with doubt, arrogance, hope, and despair. The Stalker, played with haunting fragility by Alexander Kaidanovsky, is a tragic figure. A man devoted to something he barely understands yet believes in with all his being.

This film is pure poetry, a film that doesn’t just ask to be watched but to be contemplated, felt, and lived with. I walked away from it in awe, knowing I had just witnessed something truly profound.

]]>

I went into this film knowing it was a courtroom drama with Brigitte Bardot at its centre, but I wasn’t prepared for how raw and devastating it would feel. This isn’t just a legal battle, it’s an autopsy of a young woman’s life, picked apart by men who never truly saw her for who she was.

Bardot’s performance as Dominique is astonishing. I’d always associated her with the carefree, almost mythical image of French cinema’s golden age, but here, she is stripped of that glamour. Dominique is impulsive, reckless, and full of contradictions. Bardot gives her such aching vulnerability that it’s impossible not to feel protective of her, even when she makes self-destructive choices.

What struck me most was how relevant the film still feels. Dominique is judged not just for the crime she’s accused of but for who she is, her sexuality, her lifestyle, her inability to conform. The courtroom scenes are suffocating, a parade of older men dissecting her like she’s an exhibit rather than a person. It reminded me of how women throughout history, and even today, are often put on trial for simply existing outside the mold.

Clouzot’s direction is sharp and unsparing, as expected from the man behind 'Diabolique' and 'The Wages of Fear', but there’s also an unexpected tenderness here. The film doesn’t just condemn societal hypocrisy, it mourns the cruelty of a world that refuses to understand people like Dominique.

By the time the final moments arrived, I felt gutted. La Vérité isn’t just about a verdict, it’s about the impossibility of fairness in a world so quick to judge. And that’s what makes it timeless in my opinion.

]]>

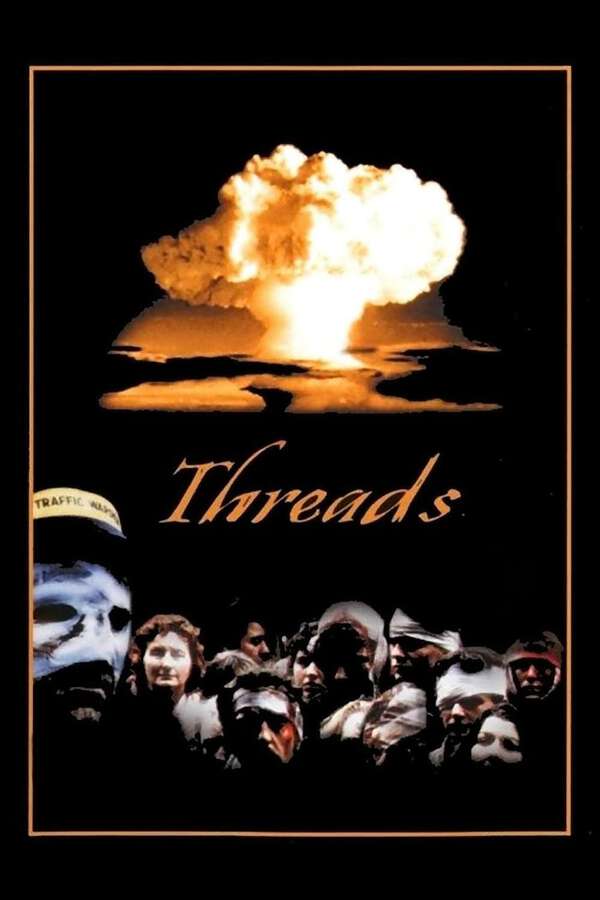

This is one of the most harrowing films I’ve ever seen. It’s not just a movie, it’s an experience that lingers long after the credits roll. It leaves you feeling hollow, shaken, and deeply unsettled. I went in knowing it had a reputation as one of the most realistic depictions of nuclear war ever put to screen, but nothing could have prepared me for just how raw and unrelenting it is.

The first half plays out like a normal UK tv drama, following Ruth and Jimmy, an ordinary working-class couple in Sheffield dealing with an unexpected pregnancy. There’s an eerie sense of normalcy as political tensions escalate in the background. News reports play, people worry but mostly carry on with their lives. That slow build-up is terrifying because it feels so real. It’s exactly how I feel a crisis would unfold. Theres warnings on the news, government reassurances and agrowing but distant dread.

Then the bomb drops, and everything changes...

The attack itself is horrifying, but it’s the aftermath that truly breaks you. The film doesn’t look away from the full, agonizing consequences of nuclear war. Radiation sickness, starvation, societal collapse. There’s no Hollywood-style heroism, no hope. Just suffering. The degradation of life is so complete that by the end, humanity itself feels like a distant memory.

What makes Threads so devastating to me is its unflinching realism. The grainy, documentary-like style only adds to the nightmare, making it feel less like a film and more like an unavoidable future we’ve somehow glimpsed. Watching it, I couldn’t shake the thought that this could have happened. This could still happen.

It’s not a film I could ever casually rewatch, but I think everyone should see it at least once. It’s the kind of film that changes you, that forces you to confront the fragility of civilization and the horrifying reality of nuclear war. Some movies entertain, some movies move you but Threads leaves something different...

]]>

Hot Fuzz is the only movie that proves small-town crime-fighting requires excessive paperwork, extreme violence, and a perfectly timed "Yarp"

]]>

Fallen Angels is a film that feels like a restless night in a city that never stops moving. It's beautiful, melancholic, and just a little bit lonely. It’s a film that washes over you like a dream, a hazy collection of fleeting connections, aching solitude, and the kind of characters who seem to live on the fringes of reality. I think it’s fantastic, even if it doesn’t hit me quite as deeply as Wong Kar-wai's Chungking Express.

Maybe that’s because Chungking Express has a gentler heart, an optimism that peeks through the cracks of its longing. Fallen Angels, on the other hand, is its moody, nocturnal counterpart. It's more alienated, more fragmented, more aggressively stylish. Christopher Doyle’s cinematography is breathtaking, drenched in neon, tilted at impossible angles, trapping its characters in a world that feels both intimate and suffocating. The film moves with a dreamlike logic, characters crossing paths in ways that feel both fated and fleeting, their desires just out of reach.

Leon Lai’s hitman and Michelle Reis’s lovelorn agent are locked in a relationship of proximity rather than intimacy, their connection defined by absence. Then there’s Takeshi Kaneshiro’s mute drifter, who injects the film with a manic, almost cartoonish energy, yet still carries an undercurrent of profound loneliness. His relationship with Charlie Yeung’s heartbreak-driven chaos is messy, ridiculous, and strangely moving.

It’s a film of contradictions. Violent but tender, absurd but deeply emotional. The ending, like much of Wong Kar-wai’s work, doesn’t offer resolution so much as it lingers in a feeling, a moment that hangs in the air like cigarette smoke. I love this movie for what it is. Hypnotic, poetic, and full of aching beauty. But for me, Chungking Express remains the one that truly captures my heart.

]]>

Watching this film for the second time, I found myself even more deeply moved by its quiet beauty. What struck me most on this viewing was how effortlessly the film captures the poetry of everyday life, how routine, when truly embraced, can become a form of grace.

Kōji Yakusho’s performance is extraordinary in its stillness. His character, Hirayama, doesn’t need grand gestures or dramatic arcs, he finds meaning in the simplest things, a tree’s shadow, the sound of water, an old cassette tape. The film slows you down, inviting you to notice the details you’d otherwise overlook.

What makes Perfect Days so special to me is how it balances solitude with warmth. Hirayama is alone, but never lonely. His quiet contentment is a rare kind of wisdom, and I felt a deep iration for his way of moving through the world. There's something profoundly beautiful about his life, not in what he lacks, but in what he cherishes.

By the final scene, I felt a quiet ache, the kind that lingers long after the credits roll. This isn’t just a film it’s an experience, one that deepens with each watch. It’s a masterpiece!

]]>It's an ever growing collection haha

- The Truth

- Late Spring

- Tokyo Story

- s Ha

- After Hours

- Seven Samurai

- Threads

- Midnight Cowboy

- The Breakfast Club

- Silver Linings Playbook

...plus 233 more. View the full list on Letterboxd.

]]>This list is in no particular order

- 28 Days Later

- Terrifier 2

- Terrifier 3

- A Nightmare on Elm Street

- [REC]

- House of 1000 Corpses

- Creep

- Creep 2

- Scream

- Scream 2

...plus 10 more. View the full list on Letterboxd.

]]>An ever growing list of my favourite comfort movies. Sit back and relax 😌

]]>This films just hit my hopeless romantic heart

]]>